After a couple of interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve (Fed) the debt capital markets are buzzing with anticipation of what it might mean for merger and acquisition (M&A) activity heading into the end of 2024 and into the new year. At MarshBerry’s recent Impact Summit, the insurance brokerage industry’s premier event on capital markets, speakers included industry capital lenders. All of them expressed their continued interest in lending for investments in the insurance brokerage industry, especially as rates adjust downward. Not that the insurance industry saw a significant disruption in M&A activity during the 19-month stretch of 11 rate increases – but cheaper cost of capital has tons of upside.

Historically, in challenging times, the insurance sector has been a place where borrowers and lenders felt very comfortable. Companies in the insurance distribution sector generate substantial free cash flow, with little to no capital expenses. This reliable cash flow creates stability and reduces the risk of default, making insurance brokerage an attractive place to deploy capital and resources.

As the Fed continues to unroll a plan to balance monetary policy against inflationary risks, the most recent interest rate cuts have helped bolster optimism in the lending sector. At the Impact Summit, lenders suggested that current rates could benefit M&A activity for the insurance brokerage industry even further, estimating an increase between 10-20% in 2025. They believe the space will continue to command modestly tighter spreads than many other sectors within leveraged finance.

Could the Fed’s plan be in jeopardy?

Now that interest rates are dropping, inflation is cooling, jobs are growing, and the stock markets are at or near all-time highs – and with the Republicans running the ship in 2025 – what could possibly go wrong? In one word: tariffs.

A week after cutting the benchmark rate by 25 basis points in November (after a 50 basis point cut in September), Fed Chair Jerome Powell hinted that another cut in December is not guaranteed. The news put a damper on the week-long stock market rally, initially sparked by Donald Trump’s presidential win and the quarter point rate cut.

Could there be cracks in the Fed’s plan to reel in interest rates now that President-elect Trump’s campaign promises might become a reality? Powell isn’t saying so, and has simply indicated, “The economy is not sending any signals that we need to be in a hurry to lower rates.” But economists and bankers are all thinking about the potential impact that the incoming Trump administration’s policies may have on economic growth and inflation – policies like higher tariffs.

Why foreign trade tariffs might be a concern

The only wrinkle in the plan for a strengthening U.S. (and global) economy might be whether President-elect Trump’s promises of trade and immigration policy changes were simply campaign pitches or something he fully intends to deliver. In his first term, then-President Trump made numerous declarations and promises, only to pivot his position or not deliver. Some believe Trump often takes extreme positions for the purpose of keeping rivals or foreign nations guessing as to what he may actually do.

Political and economic experts believe Trump will have his hands full in his first year trying to permanently extend the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) of 2017, set to expire at the end of 2025. Something he will need (and will most likely get) congressional support for.

However, if Trump intends to push forward with his proposed 20% universal import tariff and possible 60% tariff on Chinese imports – he will have absolute power to do so. The Reciprocal Trade Agreements Act of 1934 authorizes the President of the United States to negotiate bilateral, reciprocal trade agreements and adjust tariffs without direct Congressional approval.1

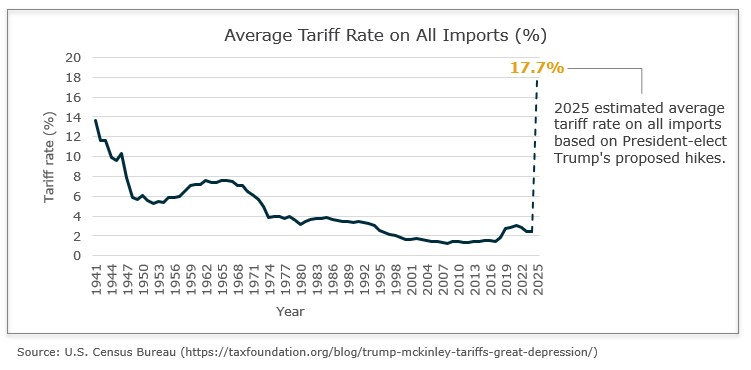

U.S. policies have historically (over the last 70 years) strived to reduce tariffs on imports, in an effort to improve economic trade both ways. In President Trump’s first term, he imposed the most significant tariffs seen in 25 years, including 25% tariffs on steel and 10% tariffs on aluminum from most countries. Additional tariffs on China in 2018 escalated a trade war between the U.S. and China. President Biden left many of Trump’s policies in place, adding other tariffs on Chinese imports for semiconductors and electric vehicles.2

But Trump’s suggested new tariffs would be an extreme reversal of the historic trend, elevating the average tariff rate to an estimated 17.7% on all imports in 2025, something not seen since the Great Depression.

Tariffs have historically been used for two purposes: Creating revenue for the U.S. (just like taxes do) and for protecting domestic manufacturers from foreign competition.

The problem is, history has also shown that most tariffs on foreign imports usually get shifted to the U.S. consumer, and often affect the prices of the domestic market. Some economic experts have predicted that such extreme trade policies would hinder economic growth, increase inflation, force another spike in interest rates, and likely ignite a new trade war.

Nothing can be said to be certain

As Benjamin Franklin once stated, “Nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” With new U.S. leadership ready to take the helm, with an economic agenda that is getting mixed reactions, nothing about the future economy is certain.

Depending on how quickly Trump uses his executive powers to institute tariffs on foreign imports, and any inflationary impacts on the economy, it may not take the Fed long to change course again on interest rates.

Currently, the Fed has projected one additional cut in 2024 and possible cuts in early 2025. But sticky inflation data from October, and now questions on Trump’s tariff policies, has some economists downgrading their bets on the frequency of additional interest rate cuts.

For now, interest rates are lower (than they were), the terms are better, and spreads have narrowed. One could make the argument that those looking for capital might consider getting it sooner-rather-than-later. For those thinking about waiting for the “last rate cut” before borrowing – it might already be here.

Sources: